Maybe it’s because of a personal bias due to my background in archaeology but the British Museum tends to put on some of the most interesting major exhibitions in London yearly; ranging from Aztec rulers to showcases of Life and Death in Pompeii or “Celtic” treasures. The Scythians however was an exhibition that was literally jaw-dropping; perhaps the main reason for this is that whilst many of the British museum’s blockbuster exhibitions conjure up imagery – with the Scythians this was just not the case, meaning every exceptional artefact came as a surprise. It left me want to go and spread the news that, scrap the Ancient Egyptians or Romans; the most amazing archaeology comes from the Eurasian steppes. Also as someone who went to a university specializing in world archaeology and which offered some pretty niche courses, the fact that the Scythians were never once mentioned, left me wondering if my university education had any more gaping holes in it.

One reason for this lack of knowledge may be connected to long-held academic divisions between the West and Russia, with the majority of these artefacts usually being displayed in St Petersburg’s Hermitage. Going around the exhibition, the most familiar exhibit was a selection of preserved tattooed skin belonging to a man of the Pazyryk culture, and linked to the “Ice Maiden” burial uncovered in 1993. The Scythians were defined in the exhibition as nomads mainly based in Siberia from the 9th-1st century BC but to me this seems rather a broad category and may explain why the aforementioned remains were known beforehand to me as Pazyryk and not Scythian.

Such spiralling patterns on human skin survive due to a Siberian permafrost, that also led to the other phenomenal survivals throughout the exhibition, featuring wood and leather and textiles that usually are only survive due to being starved of oxygen and therefore causes of decay in their frozen burial environment. Here however richly embroidered saddle covers, a child’s fur coat and ceremonial horse headgear, decorated with a felt ram and cockerel had all survived. Other stand-out groups of artefacts were the amazing gold ornaments, many of which were gargantuan belt buckets featuring scenes of interlaced beasts and warriors often engaged in combat, and surrounded by inlaid gems and glass, often in a manner startlingly reminiscent of the creatures of early Anglo-Saxon art.

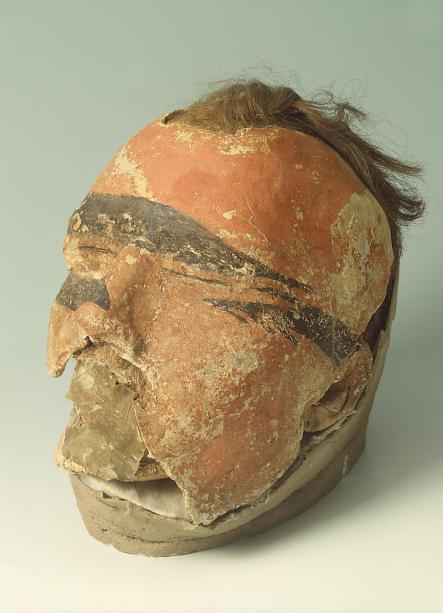

Aside from the gold and embroidery, it was examples of more “everyday” life that held their own, the remains of specialised hemp-smoking tents and a leather bag still found to contain lumps of cheese. Personally and slightly annoyingly, the most interesting exhibits of all weren’t even Scythian but the remains of the burials of those who came next… the Tashtyk culture. It always amazes me the myriad of ways in which humans have come up with of disposing of the human body and the connected rituals. The Tashtyk buried their dead with lifelike clay masks and while some were directly inhumed, other had their cremated remains placed into life-size dummies which were subsequently buried.

The question of what happened to the Scythians is never directly answered and although there is suggestion that they were wiped out by Turko-Mongol invasions, modern central Asian populations show a mix of genetics origins suggesting the Scythians may have slowly assimilated and evolved into other named groups.

In all honesty, this description of the exhibition only scratches the surface of what I saw and learned in a seemingly whirlwind post-work visit during the British Museum’s Friday late opening. My advice would be that this is an exhibition that needs to be seen in the literal flesh.

Rating: 5/5